Why Brazil has a big appetite for risky pesticides

In this farming superpower, agricultural chemicals - including paraquat – face lax regulation.And in the rural northeast, rampant use has led to sickness and violence.

LIMOEIRO DO NORTE, Brazil – The farmers of Brazil have become the world’s top exporters of sugar, orange juice, coffee, beef, poultry and soybeans. They’ve also earned a more dubious distinction: In 2012, Brazil passed the United States as the largest buyer of pesticides.

This rapid growth has made Brazil an enticing market for pesticides banned or phased out in richer nations because of health or environmental risks.

At least four major pesticide makers – U.S.-based FMC Corp., Denmark’s Cheminova A/S, Helm AG of Germany and Swiss agribusiness giant Syngenta AG – sell products here that are no longer allowed in their domestic markets, a Reuters review of registered pesticides found.

Among the compounds widely sold in Brazil: paraquat, which was branded as “highly poisonous” by U.S. regulators. Both Syngenta and Helm are licensed to sell it here.

Brazilian regulators warn that the government hasn’t been able to ensure the safe use of agrotóxicos, as herbicides, insecticides and fungicides are known in Portuguese. In 2013, a crop duster sprayed insecticide on a school in central Brazil. The incident, which put more than 30 schoolchildren and teachers in the hospital, is still being investigated.

“We can’t keep up,” says Ana Maria Vekic, chief of toxicology at Anvisa, the federal agency in charge of evaluating pesticide health risks.

FMC, Cheminova and Syngenta said the products they sell are safe if used properly. A ban in one country doesn’t necessarily mean a pesticide should be prohibited everywhere, they argue, because each market has different needs based on its crops, pests, illnesses and climate. Helm, based in Hamburg, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“You can’t compare Brazil to a temperate climate,” says Eduardo Daher, executive director of Andef, a Brazilian pesticide trade association. “We have more blights, more insects, more harvests.”

Public-health specialists here reject that argument. “So what if the needs of crops or soils in Brazil are different?” says Victor Pelaez, a food engineer and economist at the Federal University of Paraná, in southern Brazil. “What’s toxic in one place is toxic everywhere, including Brazil.”

WIDESPREAD VIOLATIONS

Screenings by regulators show much of the food grown and sold in Brazil violates national regulations. Last year, Anvisa completed its latest analysis of pesticide residue in foods across Brazil. Of 1,665 samples collected, ranging from rice to apples to peppers, 29 percent showed residues that either exceeded allowed levels or contained unapproved pesticides.

Since 2007, when Brazil’s health ministry began keeping current records, the number of reported cases of human intoxication by pesticides has more than doubled, from 2,178 that year to 4,537 in 2013. The annual number of deaths linked to pesticide poisoning climbed from 132 to 206. Public health specialists say the actual figures are higher because tracking is incomplete.

The pressures are clear here in Limoeiro do Norte, a town in the arid northeastern state of Ceará. The state used to be anything but a  breadbasket. But since the 1990s, Brazil has built a system of irrigation canals in the area, and farming has flourished. So, too, has pesticide use.

breadbasket. But since the 1990s, Brazil has built a system of irrigation canals in the area, and farming has flourished. So, too, has pesticide use.

In November, a federal court upheld a ruling that forces Fresh Del Monte Produce Inc, the global fruit giant, to indemnify the widow of a worker whose liver failed after repeated handling of pesticides. In Limoeiro do Norte, a state court is weighing charges against a landowner accused by police of ordering the murder of an anti-pesticide activist.

“This is a giant laboratory for the worst of industrial-scale agriculture,” says Raquel Rigotto, a physician and sociologist at the Federal University of Ceará in Fortaleza, the state capital. Rigotto says her research team has found traces of many pesticides in water taps in the area, and a higher rate of cancer deaths there than in towns nearby with little farming.

The world has much riding on Brazil’s food boom. The population is expected to rise nearly 30 percent over the next three decades, leaving 2 billion more mouths to feed. Brazil’s booming agricultural sector will be a critical source of nourishment. But with its equatorial sunlight, steady temperatures and year-round harvests, Brazil is also a fertile place for insects, fungi and weeds. To keep them at bay, farmers are applying more and more pesticides.

A POWERFUL LOBBY

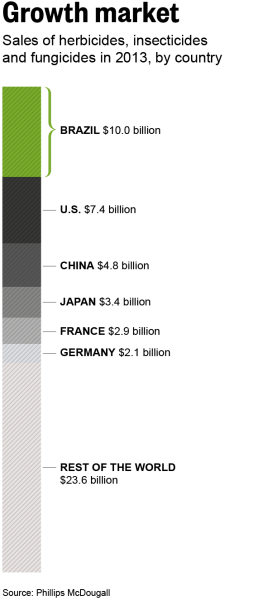

In 2013, the last year figures are available, Brazilian buyers purchased $10 billion worth, or 20 percent of the global market. Since 2008, Brazilian demand has risen 11 percent annually – more than twice the global rate.

One factor blocking more forceful safeguards is Brazil’s increasingly powerful agricultural lobby.

In last year’s elections, agribusiness trailed only the construction industry as a source of donations for the re-election of leftist President Dilma Rousseff. Brazilian food and agricultural companies accounted for about a quarter of the money she received from big donors, or 89.5 million reais, electoral filings show. That figure is based on an analysis of the 118 largest donations to Rousseff’s campaign, equal to 1 million Brazilian reais ($300,000) or more each.

In Congress, nearly half the 594 lawmakers identify themselves with the “rural bench,” a legislative faction that has relaxed laws banning genetically modified crops and loosened limits on the clearing of rainforest and other woodland. The rural bench has also proposed legislation to streamline pesticide regulation under one agency, instead of current laws that empower Anvisa and the agriculture and environment ministries.

Rousseff's press office declined to comment, referring questions to the agriculture ministry. Décio Coutinho, a senior ministry official, said in an e-mail that the use of pesticides follows "rigorous laws" in Brazil and is overseen by technicians, scientists and public servants who "enjoy the respect and total confidence of the domestic and international scientific community and Brazilian and foreign consumers."

The relationship between agribusiness and the government, including campaign donations, is "ethical and transparent," he said. There is nothing improper about the sector’s voice in Congress, he added, saying that representation "is defined by the free and sovereign vote of the electorate."

The industry’s influence, and tight budgets for regulators, limit Brazil’s ability to enforce pesticide rules.

“FARMERS LOVE IT”

Consider the time it takes Anvisa to evaluate a proposal by a manufacturer to sell a pesticide in Brazil. By law, the agency is supposed to analyze a new chemical in no more than 120 days. Anvisa can take years. With fewer than 50 scientists, compared with hundreds at comparable agencies in the United States or Europe, it has a backlog of more than 1,000 chemicals awaiting review.

It can also take years to get dangerous chemicals off the market.

An effort to re-evaluate 14 controversial pesticides used in Brazil, most of them banned elsewhere, is now in its seventh year, slowed by lawsuits from manufacturers and opposition by many lawmakers. “If it’s not a court case, it’s a congressional hearing,” says Vekic, the toxicology chief at Anvisa.

So far, the re-evaluation has led to bans of four pesticides. In December, Anvisa said it would prohibit methyl parathion, an insecticide banned in the United States and Europe. But Anvisa hasn’t yet said when or how it will act.

As a result, Cheminova, the Danish company that sells methyl parathion, has “not changed plans regarding the business with this product,” says Lars-Erik Pedersen, a spokesman. He adds that demand is now high because of boll weevil attacks on cotton. “The farmers love it,” he says.

The delays at Anvisa, farmers and pesticide companies say, force growers to keep using older, potentially more harmful chemicals because safer, more efficient pesticides are awaiting approval.

“We have new products, but there is a backlog to get them to market,” says Antonio Zem, president of the Latin America unit of FMC, the American manufacturer of Furadan, an insecticide. Furadan is based on carbofuran, a compound for which the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, after a review beginning in 2006, “concluded that dietary, worker, and ecological risks are unacceptable for all uses.”

FMC says that it has been trying to limit sales of the potent chemical to big farms and to sectors, such as sugarcane, where application can be handled mostly by machine.

DEATH OF A FARM WORKER

Furadan is one of the many pesticides used on farms along the Chapada do Apodi, a fertile plateau in eastern Ceará. There, thanks to 40 kilometers of canals fed by the nearby Jaguaribe River, more than 4,500 farmhands work fields on 324 properties.

The farms have brought jobs and some prosperity to a once-destitute region. The town of Limoeiro do Norte was once known as the “land of bicycles” because residents couldn’t afford cars. Today it hums with the tread of pickup truck and SUV tires.

But little other public infrastructure has followed the canals. As a result, many of the region’s residents get their water from the same open-air canals that irrigate the farms.

Problems along the plateau emerged as early as 2008. Agricultural workers and neighbors of farms began complaining to local church officials and labor organizations that they were developing rashes after taking showers, while their farm animals were getting sick.

That July, Vanderlei Matos da Silva, a 31-year-old employee of Fresh Del Monte Produce, reported suffering headaches, fevers, a swollen belly and yellow eyes. For the previous three years, he had worked for the company stocking a pesticide warehouse at its pineapple plantation on the plateau.

The job, according to documents and testimony by fellow workers submitted to a federal labor court, included mixing chemicals and preparing backpack dispensers for those who sprayed them. Silva also cleaned the warehouse and often stored unused chemicals in open containers, workers testified.

The fumes often made him and colleagues dizzy. “Dust from the agrotóxicos stayed in the air,” testified José Anaildo Silva da Costa, one of the workers. Another worker, Francisco Ricardo Nobre, testified that plantation managers ordered employees to hide certain pesticides when they got wind of a pending inspection.

Fresh Del Monte, based in Coral Gables, Florida, declined to comment.

A RECEIPT FOR PARAQUAT

One of the pesticides, according to worker testimony, was paraquat. A decades-old herbicide, paraquat is banned in the European Union and restricted for most uses in the United States. In Brazil, Syngenta, Helm and three other companies are licensed to sell it. The chemical is among those under review by Anvisa.

Paraquat is “highly poisonous,” according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among other ills, according to the CDC, paraquat causes kidney, heart and liver failure.

At least some of the paraquat sold to the Fresh Del Monte operation during Silva’s employment there came from Syngenta, according to a 2007 sales receipt for 25,840 reais worth ($8,160) of the chemical. The receipt, obtained by prosecutors, was reviewed by Reuters. Syngenta declined to comment.

By August, Silva could no longer work. In October, he was admitted to a clinic in Limoeiro and moved three weeks later to a bigger hospital in Fortaleza. He died a month later, leaving a one-year-old son and a widow, who began a years-long effort to win back pay and damages from Fresh Del Monte.

The official cause of death was listed as liver and kidney failure and digestive hemorrhaging. Fresh Del Monte declined to comment on Silva’s death. In court, the company’s lawyers alleged that Silva had been diagnosed with a viral form of hepatitis unrelated to his work. The judge rejected that argument.

Nearby, Jose Maria Filho, a family farmer on the plateau, had begun complaining to local authorities about sick farm animals and rashes. He accused large landowners of overusing pesticides, particularly with crop dusters that rained chemicals down on the canals and other areas adjacent to farmland.

“YOU ARE MESSING WITH BIG PEOPLE”

“He had a big mouth,” recalls Luiz Girão, a local cattle rancher and former congressman who is influential among area growers.

Filho succeeded in getting the scientists led by Rigotto to research the water on the plateau. One study they conducted in late 2008 analyzed samples taken from 25 points along the canals and from household water faucets.

The study tested for the presence of 22 different pesticides. In each sample, researchers said they found residues of at least three of the compounds and as many as 12. Area growers dismissed the study, arguing the research didn’t determine the concentration of each chemical in the water, therefore proving nothing about toxicity.

Throughout 2009, Filho continued speaking out. He appeared at town council meetings in Limoeiro, and by November had convinced enough council members to pass a ban on cropdusting, despite the opposition of big landowners.

“They were furious,” recalls Reginaldo Araújo, a local teacher and labor activist.

Some growers kept dusting anyway.

In early 2010, Filho began taking photos and shooting video of a crop duster taking off from a local airfield. He told people he was gathering evidence about pesticide violations. He also started receiving threats.

According to a police investigation detailed in an indictment reviewed by Reuters, an anonymous caller phoned Filho and told him he was being followed. The caller said Filho was tailed as he traveled local roads by motorcycle, often carrying his young son. “You are a coward because you never travel alone,” the caller said.

At the airstrip, according to a complaint Filho filed with police, a security guard warned him: “You are messing with big people. It’s  dangerous.”

dangerous.”

GUNNED DOWN

On April 21, as he rode home through sprawling banana plantations, Filho was shot 25 times with a .40 caliber pistol. His body fell on the road.

A month later, the council revoked the cropdusting ban.

After a two-year investigation, police charged João Teixeira, a local landowner, farmer and businessman who coordinated the cropdusting on the plateau, with ordering the hit. Using ballistics and cellular telephone records, prosecutors said in the indictment, police pieced together calls among Teixeira’s foreman, two locals and a hit man. Teixeira and three others were indicted in Filho’s murder.

Teixeira, reached by telephone, said: “We had nothing to do with it.” He declined to discuss the case further. A judge in Limoeiro is expected to decide in coming months whether the case will go to trial.

Meanwhile, two courts have ruled in favor of Gerlene Santos, the widow of Silva, the Fresh Del Monte worker. In 2013, a court in Limoeiro ordered the company to pay damages totaling roughly 350,000 reais, or about $110,000. A higher court recently upheld the ruling.

Along the plateau, tensions continue.

Tropical Nordeste, a plantation that exports bananas to Europe, recently won a prize from a foreign buyers’ association for excellence. In October, a worker at the plantation posted on Facebook photos he took of a leaking pesticide tank at a warehouse.

The worker, 25-year-old pesticide sprayer Diego Oliveira da Silva, said in an interview that foremen also asked him and colleagues to use up their stock of Furadan, the FMC chemical, in the days before an inspection. Two other workers, who asked to remain anonymous, made the same claim. Da Silva was fired for posting the photos.

Hugo Carrillo, manager of the plantation, said the leak was a temporary problem caused by a broken tap, fixed the same day.

As for the allegation that the plantation covered up the use of risky pesticides, Carrillo said: “Why would I hide Furadan? It’s not banned in Brazil.”

Edited by Michael Williams

The persistence of paraquat

By Paulo Prada

One of the oldest and most widely used pesticides in the world is also one of the most toxic and controversial.

Paraquat, a herbicide used to control weeds since the 1950s, was banned in the European Union in 2007. It is restricted for use only by licensed technicians in the United States and, since 2012, many of its formulations in China are being phased out.

Known for its toxicity to vital organs, including the liver, kidneys, heart and respiratory system, it is deadly if ingested and has long been criticized by public health experts. They say farm workers, especially in less educated and less regulated markets, are at risk if they use the chemical improperly.

“It’s terribly toxic,” says Mark Davis, senior officer for pesticide management at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. “Once it is in your body there is no antidote.”

“It’s terribly toxic. Once it is in your body, there is no antidote.”

Mark Davis, U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization

Paraquat caused a public health scare in the United States in 1970s: Mexican drug enforcement authorities, with funding from the U.S. government, sprayed the chemical on marijuana that later crossed the border. In the 1980s, paraquat was the agent in suicide and murder scares in Japan.

Paraquat is still widely used across much of the developing world, especially in Asia and Latin America. It is popular because it kills weeds on contact and breaks down fast once it enters the soil.

The chemical is also increasingly used to complement other popular herbicides, such as glyphosate, more commonly known by its original brand name, Roundup.

That product, developed by U.S.-based Monsanto Co but now also made by generic manufacturers, is the world's most widely used herbicide. It is commonly applied to genetically modified strains of soybeans, corn and other produce engineered to withstand glyphosate and grown on the massive, single-crop farms that dominate global agriculture today.

But glyphosate itself is controversial. Last month, the World Health Organization said glyphosate is "probably carcinogenic to humans," prompting the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to say it will seek new rules for its use.

And after years of exposure to glyphosate, many weeds have developed resistance, leading to renewed use of paraquat and other complements.

Global sales of paraquat, according to a study commissioned by the Australian unit of Syngenta AG, one of the many manufacturers of the chemical, totaled $640 million in 2011. The global market for all pesticides in 2013 totaled $54.2 billion, according to market researcher Phillips McDougall.

Original report: http://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/brazil-pesticides/#pesticideland-video